5 reasons why an asset management system is vital for your business.

- Francis McDowell

- Nov 26, 2020

- 11 min read

An asset management system[1] is the gift that keeps on giving, yielding returns in performance, costs and risk management

This article explores the argument for the introduction of an asset management system to improve business performance and examines the impact of an AMS on five problem areas.

Background

The health of a business is visible in its balance sheet which is the final proof that value is being delivered back to the shareholders/stakeholders, so our perspective in this article is to consider balance sheet performance as the paramount consideration. In the private sector, the balance sheet is a primary influence on executive strategy; in the public sector, where public assets are under agency governance, we regard the balance sheet and accompanying financial attestations of compliance with standing directions as the closest indicators of performance[2]. To introduce the case for an asset management system we take a look at the company balance sheet first and identify in simple terms the areas on it that are impacted by the quality of asset management.

In Figure 1 we can see that the assets owned by any business fall into two main categories: fixed and current assets. Current assets are those that can be converted into cash within a short amount of time, while fixed or non-current assets refer to assets acquired for long-term use. Non-current assets are directly associated with the revenues and costs of an organisation as they usually include property, plant and equipment and they usually attract costs and provide services. These assets require maintenance and renewal at regular intervals throughout their lifecycle. If the services are chargeable, there is a direct relationship between costs and revenue.

We would assume that Australian organisations are very interested in achieving the best use of all assets, especially non-current assets and ensuring their outputs are delivered at the right quality and at the lowest possible cost and risk because they impact balance sheet performance. However, the relationships that exist between revenues, costs and assets in most organisations are often difficult to identify as information is scattered throughout the enterprise and they require research, modelling and a common language to interpret. This is often problematic as organisations typically comprise silos or “tribes” of engineers, finance staff, management and maintenance staff each speaking their own language and making decisions based on local data and requirements. The relationships between assets and the services that they support, between functional and strategic objectives and between corporate and asset risk evaluation methods are often vague or not understood. This points to a need to have a management system that ties these stranded areas together so that strategic decisions can be made about assets and services based on collaborative approaches. This avoids the risks captured in the figure below

Each of these risks has an impact on performance and in asset rich organisations, lack of an asset management system causes systemic weaknesses. The impact is multi-dimensional and there is a multiplying effect as impacts resonate through the organisation and reach the balance sheet.

Organisations learn to live with poor asset management and can endure while performance is not being measured and the impact may not be visible until the specific questions about asset utilisation and efficiency are asked or transformational change introduces new performance measures that reveals the gaps.

The responses to the five questions below explore this in more detail and identify some of the issues that happen if an AMS is not present.

1. Goals and objectives are conflicting without an AMS

Most organisations engage in regular planning activities to decide annual and strategic plans. Strategic planning sets out the overall goals for the business, while annual plans more resemble the business plan or the detailed roadmap that the organisation will need to follow. The leadership team receives the organisational goals from the board and builds a delivery plan. The discussions that follow involve trade-offs and negotiations that are based on the intuition and experience of functional managers informed by historical and curated data. Each department competes for resources to deliver its ring-fenced responsibilities within the allocated budgets and the alignment of the organisation’s purpose with its assets becomes unimportant. Everyone is doing the right thing for their department, using their expertise to negotiate the best possible terms, but the ground has shifted to territories, budget, costs and resources. The goals and objectives are set for each department and changing the boundaries requires detailed reworking and nobody wants to go there, resulting in a siloed approach to decision making and competing asset management approaches

The introduction of an AMS changes the nature of the goal-setting discussion. Defining capability is based on a two-way dialog between leadership and workforce. The management team, empowered with the stakeholder needs looks for the endorsement of capability from the functional teams to deliver the services required. The managers’ responses are based on the alignment of the assets with the service goals and the identification of any gaps in technical and financial resources. Discussions include the impact of the total cost of ownership of assets, their required performance and likely operational risk both at an asset and a service level. If any of these parts are missing, the ‘big picture’ view (figure 3) cannot be achieved. If they are all present, this gives the leadership the ability to make risk-based decision and the necessary adjustments can also made to the strategic plan. This alignment of strategy, goals and risks is possible when the organisation uses a common language and a common and reliable set of asset information.

2. Organisations don’t know what assets they have, where they are, what condition they are in and what their value is.

The efficiency of businesses depends on asset utilisation and it is essential to know where assets are, what condition they are in and what their value is. No one would disagree with this but maybe it comes as a surprise to find out that recent research shows that Australian businesses lose an average of $4.3bn in assets every year; the figure below shows the distribution.

These assets are either misplaced or stolen and the numbers give us an insight into the scale of the problem. This survey was performed across 470 Australian businesses with more than 20 employees and on average this equates to $25.5m losses per organisation; this type and size of loss should show up in the balance sheet of any organisation.

An asset tracking system is part of the answer to this issue, but an integrated response provided by an asset management system is also required, including:

Identification and management of risk

Production of accurate and detailed audits

Removal of ghost assets

Management of the asset lifecycle

Identification and management of risk in this context means the evaluation of both the likelihood of asset losses and the consequence of losing them. As risk assessment is a multi-disciplinary activity, it involves all the relevant organisational functions who make a recommendation to the steering group to leverage the right features of the tracking system. This places responsibility in the business function to develop the requirements that will drive the system investment required.

Production of accurate and detailed audits in this context includes the development of a well -structured brief for the auditor including clearly articulated requirements and a method to test the quality of the audit as part of the handover. Obvious although this seems, often there is a gap in understanding between the service supplier who has a standard survey model and the client who will want a specific outcome. Assuming the experience and domain knowledge of the auditing contractor is adequate, the information should be provided in a format that can be entered into the client’s system without manual intervention.

Removal of ghost and zombie assets in this context is the removal of assets that exist in the general ledger but are not physically present or have been rendered unusable, or assets that are physically present but not recorded in any accounting records. For both of these asset types, the organisation can be either paying unnecessary taxes or carrying unnecessary risk. The AMS provides the discipline to capture the right type of asset data and make it accessible to interested stakeholders. This is done by applying a data specification across the business that is approved by steering group as a common data set for the lifecycle of the assets.

Management of the asset lifecycle in this context means the governance that supports asset lifecycle management. The key enabler for good decision making during the lifecycle is reliable data. What makes reliable data possible is a clear statement of intent by the organisation towards its assets and a strategy that explains how to convert organisational objectives into asset objectives. That way the organisation knows what to measure and report. The information systems, procedures and skills that underpin the AMS rely on this alignment to deliver capability. Although we often hear about IT platform limitations, it is usually competing objectives that have caused the issues rather than technical limitations. At some point down the line, these issues have become mis-translated as integration, functional or operational issues.

3. Organisations spend more time reacting than planning

Reactive maintenance resources, or ‘fix-on-fail’ approaches to service can average a third or more of the required resources in a proactive servicing model[3]. This is an undesirable reality that stretches resources across the whole program. However, it’s not just the financial cost that’s important; applying the risk test by assessing the likelihood of failure occurring and its consequential service impact reveals that the impact on service can be more serious than just an over commitment of resources. In service industries it can mean the cost of losing a client. Organisations can have a “do whatever it takes” approach that kicks into action when failures occur but which masks the real issue which is lack of policy, planning and procedures. The technical team are the heroes who keep the service up and running, but the real cost and impact is unknown to the organisation because it’s not measured until disaster strikes.

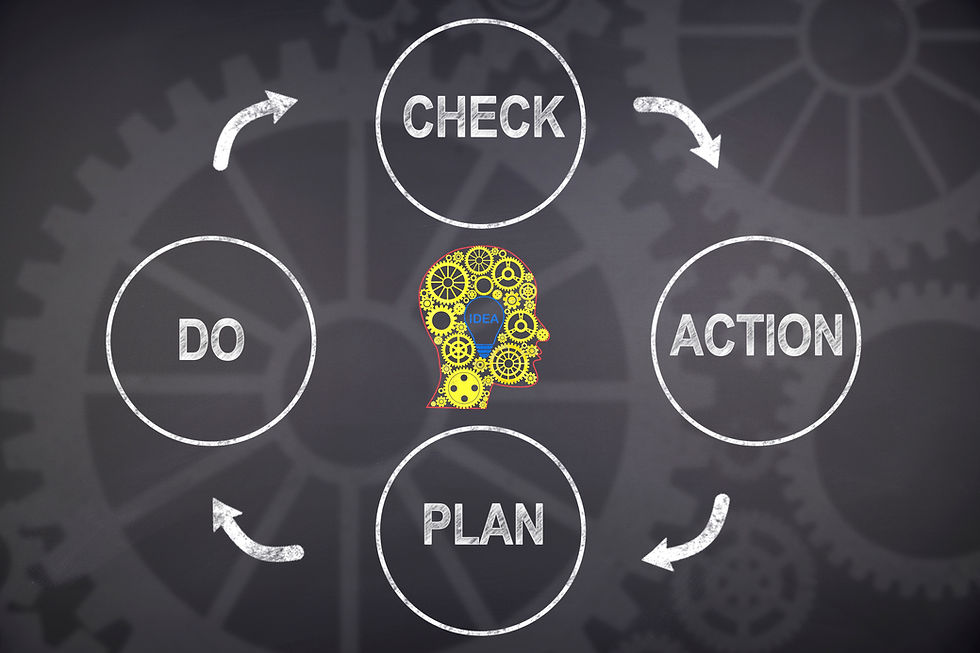

To this situation, an AMS brings the Plan Do Check Act discipline, beginning by identifying what performance is expected of assets to reach the service goals. When this is defined, the level of assurance can be set and the balance between planned and reactive maintenance established. Figure 5 describes the AMS elements, some of which are involved in making this assessment.

The assessment uses the AMS elements to determine a balanced approach to asset maintenance. The most important aspect of this planned approach is that the results can be measured, as the AMS has its own performance goals that govern how well the elements are working to deliver asset management.

4. Organisations cannot tell if too much or too little money is being spent on assets because they don’t know the total cost of asset ownership

The total cost of ownership (TCO) of assets is often one of the most difficult pieces of information to establish due to the way that large organisations have information scattered across departmental functions and systems. However, understanding TCO can make the difference between costly and timely asset replacement decisions. Some of the challenges that organisations have to manage to identify TCO are:

Information about capital and maintenance costs are captured in different systems that do not communicate with each other

Labour costs for maintenance activities are often not captured at all against the asset

Design costs are often not captured as they may be considered internal sunk cost

Local manipulation of data from different systems by different departments produces variable results

Finance, engineering and service teams interpret data differently depending on their understanding of asset lifecycle costs and their financial objectives

There is no data specification that describes the data, its purpose and use

In most organisations, the information systems that provide financial information have become silos dedicated to a specific business area; this gives the organisation a problem. In the absence of reliable data about asset lifecycle costs, it could be replacing assets too early or leaving it too late and paying maintenance costs that are too high. Where systems are not integrated, much time is spent seeking, interpreting and reporting financial information. This creates doubt about the true cost of assets which means that organisations can rarely identify what it costs to provide a service. This impacts business planning activities, especially when trying to plan new services.

What does an AMS bring to this? The figure above demonstrates the range of costs that need to be identified and these costs are usually derived from internal accounting and suppliers. Organisations typically consider that costs are those charged by outside suppliers for acquisition and operation but to get a true picture of the asset lifecycle and service cost it is necessary to capture all the costs from all parts of the lifecycle including internal functions. This cost build up occurs as follows:

The organisational strategic plan identifies the organisation’s goals and the AMS provides the policies, methods and processes to translate these into asset outcomes.

To ensure that this can happen, the AMS arranges assets in logical classes, and identifies their taxonomy so that the costs are attributed to the right parts of the asset.

Assuming that information systems are configured appropriately, the data is captured and a complete picture of asset ownership cost is available.

The cost information that is now possible creates opportunities for improvement in a number of areas:

Leverage supplier performance – By understanding what suppliers are charging for and comparing with the required level of service, organisations can optimise service charges where appropriate

Optimise service delivery – By understanding how to calculate the impact of risk upon service performance, managers can reduce or improve service outputs, set targets and monitor performance

Define an acceptable level of risk – By being able to identify how to measure the performance of services and assets accurately, the level of acceptable risk can be achieved at the right cost

5. Organisations don’t have the information, systems and processes to define a maintenance strategy

‘The need for assurance arises from the need to effectively govern an organisation. Assurance applies to assets, asset management and the asset management system’[1]. This is the goal of all organisations, especially when dealing with outsourced supply of maintenance services. In many cases, however, the suppliers have been given power to decide on the type of service required for critical assets and organisations have been disempowered, preferring to rely on the management expertise of providers rather than drive the strategy themselves. Strategy, process and systems then rests with the supplier who provides general information about assets through portals or high-level reports. To understand the potential risk that this brings it’s worth discussing a Supplier Risk Management study, where it was found that 80% of respondents believed that they had been overbilled by their suppliers and 55% had experienced significant supply chain disruption over the last three years[2]. This example highlights the problem with this arrangement - the supplier has no understanding of the client services that their assets support and therefore no ability to define the service delivery risk associated with the asset. Whilst the impact of this issue is not perceived in the short term, the lack of controls is quickly evident at a leadership level if an asset failure leads to a significant interruption of service. To avoid this, organisations often decide to adopt a ‘gold-plated’ maintenance service which may not be necessary and will be expensive.

To this situation, an AMS provides methods, procedures and controls that bring strategy and service planning in house, regulates suppliers and takes back control over maintenance regimes. The AMS governs the supplier activity by implementing performance indicators about asset performance that align with service goals and requests performance reports that are tailored to service outcomes and can be used for planning and continuous improvement activities.

Conclusion

The thrust of this article has been to demonstrate what happens to performance when there is no AMS governing assets and services. We started by describing the impact assets have on balance sheet performance and described five scenarios which directly or indirectly contribute to that performance. The important factor in all of this is that that by implementing an AMS, the organisation has the right information about assets based on the proper alignment of objectives and is empowered to make good decisions about service quality, costs, risks and growth.

[1] An asset management system is the inter-related elements of the business such as policies, plans and processes that guide decision-making about assets

Comments